Lately, a troubling piece of propaganda has resurfaced online: the claim that Harriet Tubman wasn’t a real person simply because “Harriet Tubman” wasn’t her birth name. This attempt to erase one of the most revered freedom fighters in American history not only ignores centuries of documented fact, it also betrays a deep misunderstanding of the brutal realities of enslavement and the radical act of self-naming.

Let’s be clear: Harriet Tubman was born Araminta Ross in Dorchester County, Maryland, around 1822. She was called “Minty” by family and others in her enslaved community. “Araminta” was likely chosen by her mother, Harriet “Rit” Green, though it’s also possible that an enslaver had a hand in assigning the name. What is certain is that neither "Araminta" nor "Ross" was hers by choice, they were either given to her by her mother or imposed upon her in a system that treated Black people as property.

As an adult, after escaping bondage in 1849, she chose the name Harriet Tubman, adopting her mother’s first name and her husband’s surname. This renaming was not just symbolic—it was an act of spiritual, psychological, and political resistance. By renaming herself, Tubman reclaimed agency over her identity in defiance of a system that had tried to erase her personhood.

And she wasn’t alone.

Sojourner Truth, born Isabella Baumfree in New York in 1797, changed her name in 1843 after experiencing a religious transformation. “The Lord gave me the name Sojourner,” she said, “because I was to travel up and down the land, showing the people their sins and being a sign unto them. And Truth, because I was to declare the truth to the people.”⁽¹⁾ Her new name marked the beginning of her public ministry as an abolitionist and women’s rights advocate, one rooted in divine purpose and self-definition.

Likewise, Frederick Douglass, born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, renamed himself after escaping slavery in 1838. The surname “Douglass” was inspired by a character in The Lady of the Lake, suggested to him by a fellow abolitionist.⁽²⁾ For Douglass, the new name symbolized both a break from his past and his entry into a new life as a free man and public intellectual.

These are not trivial matters. Under slavery, names were frequently changed by enslavers to mark ownership, erase African heritage, or sever family ties. Naming was part of the machinery of dehumanization. In contrast, renaming oneself was an assertion of humanity. It was a way to reclaim one’s story, one’s dignity, and one’s power.

So no, Harriet Tubman wasn’t born with that name, but the name she chose is more significant than any she was forced to bear. Her life’s work under that name, guiding over 70 people to freedom, serving as a Union spy, and later advocating for women’s suffrage, is documented in government reports, interviews, and newspaper accounts.⁽³⁾⁽⁴⁾

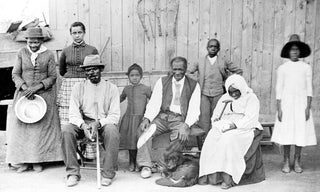

The 1868 Report of the Joint Special Committee on the Conduct of the War includes her contributions to Union military efforts. Interviews conducted by Sarah Bradford for Scenes in the Life of Harriet Tubman (1869) contain firsthand testimony from Tubman and those who knew her. Advertisements offering rewards for her capture exist in historical record—including one we included in the Hoodoo Almanac 2025, dated 1849, when she escaped Maryland with her brothers (shown below).

Notice published by Harriet Tubman's enslaver Eliza Brodess in the Cambridge Democrat (1849) offering a reward for the return of Harriet Tubman (Minty) and her two brothers. Public domain.

Harriet Tubman also received a pension from the U.S. government in recognition of her work as a nurse and spy for the Union Army, a bureaucratic trail that could not have existed if she were imaginary.⁽⁵⁾

Let’s be crystal clear: Black women don’t have to prove their reality to anyone, especially not to armchair skeptics spinning conspiracy theories on social media or those posting nonsense for clicks and clout. Harriet Tubman’s name change wasn’t an erasure of identity, it was the embodiment of freedom, legacy, and intent. The name she chose is inseparable from the impact she made.

Birth names are historical footnotes. Facts and deeds are what make someone real.

References

-

Nell Irvin Painter, Sojourner Truth: A Life, A Symbol (New York: W.W. Norton, 1996).

-

Frederick Douglass, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave (Boston: Anti-Slavery Office, 1845).

-

Sarah H. Bradford, Scenes in the Life of Harriet Tubman (Auburn, NY: W.J. Moses, 1869). https://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/bradford/bradford.html

-

U.S. Congress, Report of the Joint Special Committee on the Conduct of the War, 1868.

-

National Archives, Record Group 15, Records of the Department of Veterans Affairs, "Harriet Tubman Pension File."